Understanding the needs of physical development in golf

To improve performance in sport there is a need to understand the physiological demands and hence apply the correct physical stimulus to enhance and support the athlete. The aims of this article are to discuss the following points:

- Why golf performance and golf training has changed

- The developments in the research surrounding golf

- Understanding strength qualities and how to train them

- Exercise classifications and how to use them in golf

- Conclusion and how to apply this information

Why golf performance and golf training has changed

The physical development of elite golfers as we know was entirely changed 20 years ago with the likes of Tiger Woods followed by Adam Scott playing on the world’s stage. Both these players changed the way that golf was being played. The primary means was due to the increased driving distances that both these players could achieve. This bought attention to the importance of physical strength and conditioning to golf. I would be very surprised if any of the world’s top twenty players are not doing some type of physical preparation to improve their performance as a result. Furthermore, this can be echoed on social media, with players such as Jordan Spieth, Ricky Fowler and Justin Thomas frequently posting brief clips on Instagram, which show a highlight reel of example workouts they have done.

The developments in the research surrounding golf

Alongside this improvement in athletic potential, the research in sports has increased and is developing. 3-D motion capture systems have helped to construct a superior understanding of what the body is doing during the golf swing and what is the most efficient technique to swing the club for that particular individual. This level of research has helped to influence the way that golfers train and condition themselves. In addition to the investigation into the golf swing, many physical performance profiling tests have been identified as key performance indicators of golf. Like other sports, there is a large number of tests that can be carried out on athletes to determine their strengths and weakness and therefore allow the optimal programme.

The two primary tests linked in the research to elite golf performance are the isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP) and countermovement jump (CMJ) (Wells et al, 2018). Enhanced performance in these tests has been correlated to an increase in clubhead speed, which is likely to improve driving distances. Consequently, these 2 tests have been used to benchmark players. This correlation is understandable as the primary group of muscles producing the force in these two tests is that found in the lower body. Of course, improvements in clubhead speed should not only be the focus of the programme for the player. There should also be a reference back to improving movement, reducing the risk of injury, and improving mental capacity by developing physical capacity.

Understanding strength qualities and how to train them

Much has been written, presented and discussed around most sports regarding periodisation and the progression of programmes (Verkhoshansky & Siff, 2009, Joyce & Lewindon, 2014). As we understand, periodisation is the systematic planning of training during the year or season to increase the chance of optimal performance (Comfort & Abrahamson. 2010, Roberson & Joyce, 2018). As such, it is essential to understand and identify the main strength qualities linked to performance for that individual before starting this planning.

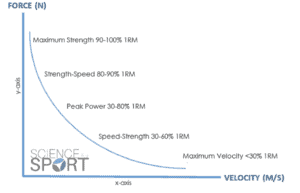

The main strength qualities are highlighted in the force-velocity curve image below. The curve simply shows visually that as velocity increases the human body’s ability to produce force is reduced, this is primarily due to the time it takes muscles to contract.

Figure 1 Force-Velocity Curve taken from the Science for Sport website https://www.scienceforsport.com/force-velocity-curve/

In some sports, the amount of force or the time to create force is not an issue and in others it is vital. For example, in powerlifting, there is no time limit to complete a repetition once the lift has been started. However, during the 100m sprint, it is favourable for athletes to produce maximal amounts of force in the shortest time possible; thus, optimising the stretch-shortening cycle during gait. Likewise, you might get some sports that need both the ability to create force and velocity as well; rugby is an excellent example of this. Players must sprint at high speeds, make tackles in defence and break lines in attack.

Moving our attention back to golf, it is clear that the sport requires the player to perform repeated explosive movements during the course of the round.

However, this does not mean that power, speed-strength or maximum velocity should be the only strength qualities that a player should focus on. Our ability to develop power is very much linked to our ability to create force and therefore our level of maximal strength. Increasing our maximal strength, it will cause the force-velocity curve to shift up and consequently, allow the player to express greater force. This increases the ability to generate more power if the athlete trains at the correct speeds of movement. Thus, over the course of the year, the player should look to develop all the different types of strength qualities.

This periodisation of the programme would then allow the player to relate back to the force-velocity curve. Which is linked in the gym to loading (amount of weight on the bar or object) and the speed of the movement (speed of the bar or object that is being moved). In basic terms, heavier lifts improve strength (which will be performed at lower speeds), and lighter loads enhance explosive movements (which will be performed at faster speeds). This is shown in figure 1. One important note: lower speeds do not mean that the player slows the lift down, all lifts should be performed with the intent to move the load as fast as possible.

Understanding the strength qualities to focus on is the first step, the next step would be to look to understand the different types of movements to use in the programme. Most players get this the wrong way around and select an exercise and then load differently.

Exercise classifications and how to use them in golf

This is where exercise classification can help. There are enormous amounts of discussion on this area, take a look at the HMMR blog posts or the work of Mel Stiff in his book Supertraining. We should, however, focus on four types of physical preparation exercises 1) general physical preparation or GPP, 2) specific preparation exercises or SPE, 3) specific development exercises and 4) competitive exercises.

GENERAL PHYSICAL PREP

Let’s first start with GPP exercises. These are exercises that if you looked at them, you would think that they would benefit from many different sports. Taking on board some of the discussion surrounding GPP exercises, it is important for the player to understand the need to complete all the main movement competencies to a high level.

Due to the nature of this classification, there is a large number of exercises. Therefore, they have great versatility and are used for developing athlete potential and recovery.

SPECIFIC PREP EXERCISES

The next is SPE. Again, exercises do not imitate the movement, however, they train the same muscle groups and physiological systems.

SPECIFIC DEVELOPMENTAL EXERCISES

SDE is the next classification. These exercises look to try to repeat or copy parts of the movement shown in the sport. The most common way to do this is by ‘overload training’ a part of the movement or adding resistance to the movement. For example, in sprinting, the coach could programme resisted sprints, where the sprinter attaches a weighted sled to themselves. In golf terms, this is the area of training that is shown on social media the most. When players are shown to imitate parts of the golf swing with added load. Example SDE could be,

Competitive Exercise

Lastly the Competitive Exercise. These are training activities that are identical to the sport. Therefore, in golf, it would be technical practice sessions or a competitive event. The primary reasons for classifications of exercises are so that coaches can help to understand the transfer of training, and which exercises will lead to this.

As coaches, we need to understand what is improving the player. There is no point in improving in the gym environment if this cannot be expressed on the course. It is also important to know when and how much of each classification to include in the programme. This will be related to the training age of the player, time of the competitive season, and level of movement competency.

We understand that context is everything when it comes to social media and we have to appreciate that a post is just a snapshot of what a player is doing. However, in some discussions with coaches, the main comment is that general physical capacity is low in golfers and that there is a considerable emphasis on using specific prep and development exercises. There are three points of importance here: 1) GPP exercises are necessary for substantial performance gains, 2) GPP are vital to allow the player to develop correct movement patterns, that allow for load and increase speed to be used and, 3) develop a physical preparation base so that when the player uses SPE and SDE exercise they would be able to get the most benefit out of them.

SUMMARY

Hopefully, this article has highlighted the changes in physical preparation in golf over the last 25 years. I have briefly discussed the research and how this has and is shaping the training for golf. The primary motivation behind this article was to highlight and discuss the different strength qualities and the different exercise classifications and how they relate to the training of the golf swing. Consequently, I hope that you have found the article of interest and useful in programming for your golfers or yourself. I would also like to add a big thanks to Chris Bishop and Pete McKnight for their help and advice regarding this article and Owen at SportsSport for allowing the use of imagines.

Drop us an email with any questions here, info@theathletetribe.com

Enjoy your training.

Lee

Reference

Comfort, P., & Abrahamson, E. (Eds.). (2010). Sports rehabilitation and injury prevention. John Wiley & Sons.

Joyce, D., & Lewindon, D. (Eds.). (2014). High-performance training for sports. Human Kinetics.

Robertson, S., & Joyce, D. (2018). Evaluating strategic periodisation in team sport. Journal of sports sciences, 36(3), 279-285.

Science for Sport

https://www.scienceforsport.com/force-velocity-curve/

Verkhoshansky, Y., & Siff, M. C. (2009). Supertraining. Verkhoshansky SSTM.

Wells, J. E., Mitchell, A. C., Charalambous, L. H., & Fletcher, I. M. (2018). Relationships between highly skilled golfers’ clubhead velocity and force producing capabilities during vertical jumps and an isometric mid-thigh pull. Journal of sports sciences, 36(16), 1847-1851.